Laila Valila: Leading & Learning at USask

A first-year graduate student at the Johnson Shoyama Graduate School of Public Policy (JSGS) and the VP Indigenous Engagement for the Graduate Students Association (GSA), Laila Valila is already making her mark. Her connection to community runs deep, and it’s shaped both her academic path and her leadership journey.

When Laila Valila began her Master of Public Administration program at the University of Saskatchewan (USask) this fall, she was motivated by a deep commitment to Métis governance, student advocacy and meaningful change.

Originally from St. Louis, Saskatchewan, with family ties to Batoche, Valila identifies as Métis, with Indigenous roots on her father’s side and Métis heritage on her mother’s. Valila demonstrated a dedication to her education at a young age, earning the Governor General’s Bronze Medal upon graduating high school in recognition of her hard work.

“I’ve always been incredibly interested in Métis Nation,” said Valila. “I voted for the first time when I was 16 and I haven’t missed a single vote. I show up to regional meetings whenever I can.”

Since arriving at USask for her undergrad in 2020, Valila has been committed to gaining experience in governance and connecting with students across campus. She has served as an executive representative on various USask clubs and student societies, including the Political Science Students Association, the USSU Indigenous Advisory Committee, the USSU Election Committee, the Métis Students Association, and USask NDP. She graduated with a Bachelor of Arts in Political Studies, with Honours, in 2025 while earning three additional certificates.

“When I came to campus, I applied for absolutely everything I could,” said Valila. “The connections I've made have been so helpful.”

Now in graduate school, Laila is pursuing a course-based Master’s in Public Administration. Ultimately, she hopes to work in federal social policy, where she can advocate for Indigenous communities on a national scale.

Outside the classroom, Laila currently serves as the Vice President Indigenous for the Graduate Students’ Association (GSA), where she serves on several sub-committees working to support Indigenous graduate students at USask.

One of Laila’s goals as VP Indigenous Engagement is to change how land acknowledgements are delivered on campus.

“There's an issue where it's always just copied and pasted in, and then is often still inaccurate when delivered,” said Valila. She believes that the current approach can feel performative, especially to international students who may not be aware of the history of the land.

“It doesn't seem like reconciliation - it seems like a requirement,” she says. “There has to be a different approach to reconciliation on campus than providing a mandatory land acknowledgement.”

Valila’s advice to other Indigenous graduate students is simple: get involved.

“Apply for anything you can, especially if you're interested in governance,” she urges. “Join an exec if you can.”

For those less inclined toward leadership roles, she recommends attending USSU events. “You can just show up on your own, and there are so many other people who are there on their own, too.”

Laila also challenges Indigenous students to think about their role in supporting one another.

"Indigenous leaders on campus are doing a wonderful job but as a collective, we are not doing enough," said Valila. "As someone from a rural community, I think this comes from a feeling of disconnection due to the individualistic nature on campus. I really encourage all Indigenous students to connect to their roots and to give back to our community and youth through campus involvement."

Kayla Benoit (she/they) is an M.Sc. student in the Department of Management at the Edwards School of Business at the University of Saskatchewan (USask). An urban member of Biigtigong Nishnaabeg (formerly Ojibways of the Pic River First Nation) in Ontario, Kayla brings a distinct and meaningful perspective to their academic work. Born and raised near Humboldt, Saskatchewan, on the border of Treaty 4 and Treaty 6 territories, Kayla has gained invaluable knowledge and wisdom from the original stewards of the lands where they live, work, and study.

Kayla moved to Regina to attend university and went on to build a career there, earning a Bachelor of Administration specializing in Human Resources from the First Nations University of Canada. She has held multiple roles at the University of Regina, worked with WCB Saskatchewan, the YMCA of Regina, and St. Peter’s College (a USask affiliate), as well as contributed to various research initiatives at USask. After the passing of her family matriarch, Kayla decided to return to her hometown of Guernsey and was presented with the opportunity to pursue graduate studies at Edwards.

Supported by an Indigenous student stipend and the encouragement of countless incredible women in the department, Kayla has thrived in her research journey. With plans to defend her thesis in January 2025, she continues to honor the legacy of her family and community through her academic and professional contributions.

Kayla’s thesis research originated from a project with the City of Saskatoon and MITACS, where she served as a Business Strategic Intern (BSI). From this work, her thesis emerged, focusing on analyzing the City of Saskatoon job descriptions by hand to identify biases embedded in language. While much existing research emphasizes the gendered aspects of bias, Kayla’s work reveals the extent to which other forms of bias—such as those related to age, location, education, and experience—are deeply ingrained in everyday language and, by extension, job descriptions. These biases subtly but significantly limit the pool of viable candidates, perpetuating systemic inequities in hiring practices.

Indigenous research in management is particularly significant, and Kayla’s work embodies this importance. By integrating Indigenous perspectives, her research challenges Eurocentric assumptions, decolonizes management knowledge, and fosters more inclusive organizational practices. These contributions help create systems that value relationality, community, and equity—key principles in Indigenous worldviews—and address systemic inequities that persist in contemporary management practices.

Looking ahead, Kayla plans to pursue a PhD in Interdisciplinary Studies, continuing to build on the work she has done with the City of Saskatoon. While she remains open to the opportunities her research may bring, Kayla is deeply committed to both advancing her academic contributions and nurturing the health and happiness of her abinoojiinyag (children) and wiijiiwaagan (partner.)

Notable Awards:

- SSHRC Canada Graduate Scholarships, Doctoral Program (CGS-D) (Offered)

- SSHRC Canada Graduate Schoalrships, Master's Program (CGS-M) (2023)

- Great West Life Business Education Bursary (2023)

- MITACS BSI (2023 - 2024)

- Edwards Indigenous Graduate Student Stipend (2022)

Kira Mudrey is an urban Métis woman from Saskatoon, Saskatchewan with strong ties to the community of Batoche, Saskatchewan. She earned her Bachelor of Science in Animal Bioscience from the University of Saskatchewan (USask) in 2023 and is now a master’s student working with Dr. Tim Dumonceaux in the Department of Veterinary Microbiology. She is also an Articling Agrologist with the Saskatchewan Institute of Agrology working towards her Professional Agrologist designation and is a trainee in the NSERC-CREATE OHAP (One Health Against Pathogens) Program which trains graduate students in One Health interdisciplinary research, communication, and public policy.

Growing up, Kira always knew that she wanted to work with animals. She had pet dogs and loved riding horses. For a long time, she thought that a career in animal health meant being a veterinarian. She thought her vet was a magic person that made her sick puppy feel better and wanted to be just like them. She attended Vet Med summer camp at USask every summer and went into the Animal Bioscience program still thinking she was going to become a veterinarian. But as she started her university career and began exploring different career paths, her viewpoint shifted. She spent time volunteering in a vet clinic and began to realize that clinical work wasn’t what she was passionate about.

By this point, she had become very interested in wildlife work and research. She had spent a few years volunteering with Living Sky Wildlife Rehabilitation in Saskatoon and developed a passion for helping wildlife. During her senior years of her undergraduate degree, she had the opportunity to take part in a course called ANBI 475: Field Studies in Arctic Ecosystems with Indigenous Peoples. She was able to get boots-on-the-ground experience in wildlife research and data collection and found it a truly transformative experience. She realized that her true passion lay in research – finding innovative solutions to problems facing wildlife conservation in Canada. Around the same time, an opportunity arose for her to join the Bison Integrated Genomics (BIG) project at USask.

The focus of the BIG project is applying innovative technological solutions to the decades-old problem of diseased wood bison (a threatened species in Canada) in northern Alberta. Wood Buffalo National Park houses the world’s largest and most genetically diverse herd of wood bison, which is at risk due to a high burden of disease. Bison are critically important species in Métis culture and many Métis traditions, customs, and governance structures are based around the bison hunt. The opportunity to participate in a project working to enhance bison health and diversity and ensure bison are conserved for future generations was an opportunity Kira could not pass up. In the fall of 2023, she began her master’s degree in veterinary microbiology developing rapid molecular diagnostic solutions to detect brucellosis (caused by the bacteria Brucella abortus) in Canadian wood bison. She is working on diagnostics that can be taken out of the lab and applied animal-side to speed up the process of detecting infected bison in this herd, with potential wider One Health implications, as brucellosis is a zoonotic disease that affects livestock and humans, and is endemic in many lower and middle income countries.

After completing her master’s degree, Kira hopes to continue working in wildlife health and using her microbiology and diagnostics expertise to apply innovative solutions that will help protect Canadian wildlife and species at risk.

"In the field of wildlife health, it is critically important to have Indigenous researchers and Indigenous perspectives because we were the stewards of this land for so many generations before Canada was ever settled. Indigenous peoples have a special relationship with and connection to the natural world and we are uniquely positioned to understand wildlife biology. We have co-existed with these species for thousands of years and understand their needs and patterns of behaviour, and our ways of knowing can often build on and help to put Western science in context.

"It is also important to remember the harms that have occurred when Indigenous voices were not at the table. It’s something I am acutely aware of when working with bison – it’s difficult to forget that settlers were the ones that hunted bison nearly to extinction and upended the lives of our ancestors, causing decades of poverty and suffering. To avoid repeating those mistakes and reopening those wounds, we must have Indigenous perspectives and Indigenous researchers working in these areas so we can work with the animals in a good way, show respect and give thanks to the Creator, and ensure we are doing what is best for them and for our own communities.

"My research also falls under the umbrella of One Health, which in many ways is a reflection of Western science beginning to adopt Indigenous worldviews. The One Health paradigm considers that the health and well-being of all things are interconnected – animals, humans, and the environment. Indigenous peoples have understood this and cared for our lands from a One Health perspective since time immemorial. Who has better insight than Indigenous researchers to see and understand the connections between all living things and take action for the greater good of all?"

Notable Awards:

- NSERC Canada Graduate Scholarships, Master's Program (2024)

- NSERC Indigenous Scholars Supplement (2024)

- CGPS 75th Anniversary Recruitment Scholarship (2023)

- Indigenous Student Achievement Award (2021, 2023)

Visit the following links to learn more about Kira and her research:

Ayicia Nabigon (she/her) is a M.Sc. student in the Department of Biology at the University of Saskatchewan from Biigtigong Nishnaabeg (formerly Ojibways of the Pic River First Nation), ON. Ayicia graduated from York University in 2022 with a B.Sc. (Hons.) in Environmental Biology. During her undergraduate degree, Ayicia worked as a research assistant on the “Improving Student Supports for Indigenous Science Students” research project (Dr. Paula Wilson) to provide feedback and suggestions for improving Indigenous student support in the sciences at York University.

After observing the moose population declining around her community, Ayicia wanted to learn more about the causes and effects of an increasing population overlap with white-tailed deer. Ayicia’s M.Sc. project is focused on examining moose and white-tailed deer habitat use and population overlap in the Boreal Plains of Saskatchewan, and the role of anthropogenic disturbance on population distributions. Her research is informed by concerns, questions, and feedback from Indigenous elders, youth, and hunters regarding food security and sovereignty, environmental change, and economic development in her study area.

Ayicia strongly believes that building and maintaining a community is critical to success. Outside of her research, Ayicia is passionate about supporting and encouraging Indigenous students in science and post-secondary education. She has volunteered as a peer mentor and facilitated workshops related to transitioning to graduate studies, applying for scholarships, and hosted peer support sessions for Indigenous students in STEM programs. Ayicia is also a participant and volunteer with the ISAP STEM+ program and is currently serving as President of the Biology Graduate Students’ Association.

"Our rights to hunt, fish, trap, and gather in Canada are inherently tied to the right to healthy and non-toxic water, land, and food. As Indigenous people, our concerns about environmental change and management are too frequently overlooked and ignored. It’s important that our communities can access the resources, policies, and spaces needed to protect the natural environment on our traditional territories. Pursuing education and careers in the natural sciences help us to expand our respective communities’ independence and expertise on relevant environmental issues. There is so much joy that comes with being able to defend and understand the natural areas that matter to you, and it is so important to keep our ecological perspectives and knowledge prominent in and beyond our communities."

Notable Awards:

- USask Indigenous Graduate Leadership Award (2024)

- NSERC Canada Graduate Scholarships, Master’s Program (2023)

- NSERC Indigenous Scholars Awards Supplement (2023)

- USask Graduate Scholarship (2022)

Jeremy Irvine (he/him) is a M.Sc. student in the Department of Plant Sciences at the University of Saskatchewan from Yellow Quill First Nation (No. 376; Treaty No. 4, Saskatchewan). Jeremy is a graduate of the University of Saskatchewan, where he completed a B.Sc. in Agriculture with great distinction. His NSERC-USRA, as well as his 4th-year thesis research, focused on plant vector-pathogen interactions. Supervised by Dr. Sean Prager, he is now working on the economic entomology of the lesser clover leaf weevil (Hypera nigrirostris) and their impacts on red clover (Trifolium pratense) seed production in the Canadian Prairies.

Jeremy grew up in Melfort, Saskatchewan, where he farms small grains and oilseeds. He is passionate about advocating for Indigenous scholars while continually working towards decreasing Indigenous underrepresentation in both post-secondary and academia. He participates in annual career fairs on his reserve to spark interest in post-secondary education and previously assisted in starting a student-led charity which provides science outreach programming to school age children. Most recently, he has authored an article highlighting the importance of integrating Indigenous Knowledge into the traditional Western scientific approach, which he hopes will result in a more inclusive and equitable academic landscape.

"Conservation practices play a critical role in protecting the ecosystems surrounding us, which helps ensure the survival of insect species that we cherish as entomologists. Too often, however, conventional conservation approaches discount the knowledge and perspectives that Indigenous people have acquired over millennia. Indigenous peoples, although only constituting 5% of the global population, protect over 80% of the world’s biodiversity (Sena 2020) and often profoundly understand the interconnectedness and dynamism between flora and fauna in a given area. When consulted, this knowledge can aid researchers in developing a complete picture of the interactions in an ecological community. Further, Indigenous inclusion and consultation are paramount in recognizing the value of traditionally acquired knowledge, which can help lead to reconciliation and promote equity in the natural sciences."

In addition to his research, he volunteers with several societies and organizations invested in protecting Saskatchewan’s native flora and fauna while simultaneously serving in an executive position of the Plant Science Graduate Students’ Association, where he advocates for graduate students and serves as a link between them and external industry partners.

Notable Awards:

- Saskatchewan Lieutenant Governor Indigenous Scholarship (2024)

- USask Indigenous Achievement Award (2024)

- Natural Science and Engineering Research Council of Canada Indigenous Scholars Award (2023)

- Natural Science and Engineering Research Council of Canada Undergraduate Student Research Award (2022)

Dr. Adam McInnes (M.D., M.Sc) is a Métis PhD student and Vanier Scholar at the University of Saskatchewan (USask), where he engages in tissue engineering and regenerative medicine research, bridging biomedical engineering and Indigenous medical anthropology.

Adam grew up on a small farm in Southwestern Saskatchewan. He serves as president of Saskatoon Métis Local 126, which supports Métis post-secondary students, staff, and faculty in Saskatoon. Through Saskatoon Métis 126, Adam is developing a research project to explore the cultural connections between Scotland and the ethnogenesis of the Métis.

As a strong advocate of interdisciplinary work, Adam has taken on leadership roles to engage with and promote collaborative and interdisciplinary learning opportunities. With the help of two of his classmates, he established the MD/MBA program at USask, which allows students to complete the two professional degrees concurrently. Adam was also a member of the University of Saskatchewan Space Design Team and SaskInvent while he was in medical school. In 2016, he helped to found Med.Hack(+), a hackathon that facilitates the development of technology to solve problems in healthcare, as well as the the Canadian International Rover Challenge during his MS.

He is currently working to establish post-secondary educational opportunities that combine engineering and health, as well as developing a STEAM education program for youth.

Notable Awards:

- Vanier Canada Graduate Scholarship (2019)

- Indigenous Graduate Leadership Award (2018, 2023)

- Queen Elizabeth II Platinum Jubilee Medal (2023)

- APEGS Friend of the Profession Award (2022)

- USask Indigenous Achievement Award (2023)

About Adam's research:

The focus on my research is in tissue engineering and regenerative medicine. Much of this research is still laboratory-based, with clinical use often still many years away, other than the odd clinical trial making use of the technology and procedures being developed. But tissue engineering and regenerative medicine have incredible promise in rejuvenating, regenerating, or even replacing damaged or diseased tissues, failing structures and organs, and missing body parts. In my research, I am developing a scaffold for growing solid organ tissues.

It might not seem at first glance that my research has anything to with Indigenous people or why Indigenous research would be imperative to my field of study, and you would be right. But once you start looking into it further, as I have recently been doing, you see why it is so important and some of the incredible research opportunities that present themselves.

We know that in many Indigenous nations, there are high rates of need for organ transplants due to chronic diseases like diabetes, but also low rates of organ donation for various cultural, historic, and systemic reasons. Research on why there are low rates of organ donation among Indigenous people has often been an afterthought. No one has looked at cultural perspectives on tissue engineering and regenerative medicine for any ethnic group—until now. I have been working on a side project to talk with First Nations, Inuit, or/and Métis community members about their perspectives on this topic to gain a cultural understanding of what this technology could mean and what we as laboratory researchers and clinicians should be considering in the development and implementation of this revolutionary technology. Instead of Indigenous people being an afterthought, we're the ones starting this discussion.

Valerie (B.Ed, M.Ed) and her daughters Kari (B.Ed, M.Ed) and Shawn (B.Ed, M.Ed) share a lifelong commitment to Indigenous education.

As they continue to pursue graduate studies together, they are embracing Indigenous knowledge and perspectives. By centering Indigenous wisdom and educational leadership, they honour Indigenous heritage and pave the way for more equitable and inclusive educational systems.

About Valerie Harper

Tanisi, Valerie Harper, nitisiyihkâson, Mistawasis Nêhiyawak ochi niya. Hello, my name is Valerie Harper from Mistawasis Nêhiyawak.

For Valerie, her ancestral relations remind her that she is inherently and spiritually Indigenous, and her ancestors are always with her providing strength, courage, guidance, wisdom, and resiliency. She is grateful to Creator God for her Indigenous identity and for all His blessings, past and present.

From her birth to present day, Valerie’s path through life has been unconventional. Growing up, she faced racism, discrimination, and prejudice which affected all areas of her life. Despite dreaming of becoming a nurse, Valerie was told she would not have the capacity to achieve more than a grade 10 education, placing an arbitrary ceiling on her learning. Feeling as if she did not belong in the education system, Valerie dropped out of high school at age 15 in 1963.

At 17, Valerie married her husband, and their family eventually grew to four children and seventeen grandchildren (including great and great, great). Valerie returned to school for upgrading and slowly felt her confidence grow as she found new opportunities to thrive.

In 1980, Valerie started as a teacher associate at a community school. In 1981, she was accepted into the Indian Teacher Education Program (ITEP) to complete a four-year degree in education. After completing her internship in the fall of 1984, she was soon offered a role to teach for Saskatoon Public Schools (SPS). Valerie believes that Spirit was guiding her path during this time, and she gives thanks for the spiritual blessings she’s received throughout her life.

After dropping out of high school at 15, completing a Bachelor of Education degree was a major accomplishment, and created the momentum that led to over four decades of further education. After starting as a teacher associate with SPS, Valerie worked for 12 years as a classroom teacher in the division. In 1997, she was accepted into graduate studies to complete at Master of Education degree in Educational Administration. In 1998, she earned a postgraduate diploma, and then graduated with her M.Ed in 1999. Graduation was an especially powerful moment for Valerie, as her daughter Kari graduated with her B.Ed. on the same day. Valerie continued to work with SPS as an educational administrator from 1998 to 2007.

In the fall of 2007, Valerie was encouraged to apply for a position with the Saskatoon Tribal Council (STC). Later that year, she took a leave of absence from SPS to join the STC as the Director of Education. For Valerie, the opportunity to work with and for her people felt like coming home. In January of 2008, Valerie moved on from the provincial education system and chose to finish her career in the federal education system, working with the seven STC First Nation communities. Valerie retired in December 2020, but continued to pursue higher education and advocacy for learning environments that provide equitable space and place for Indigenous children to excel, realize their potential, and achieve their dreams.

Valerie is now in her final year of a Doctoral program, using her own life story as her dissertation. She looks forward to celebrating this momentous achievement at graduation, where her eldest daughter, Shawn, will also receive her doctorate in educational leadership.

“I have come a long way from the little Indigenous girl who grew up on the Fox Farm in Prince Albert. I have been blessed with a beloved five-generation family. My warrior daughters Shawn and Kari, and warrior son, Jason walk hand-in-hand with me on Mother Earth. My beloved husband, son, and mother are in Spirit world with our ancestors, all of whom give me strength, courage, hope, wisdom, and resiliency to stay true to my teachings. I am honoured to have had some true mentors in my life who supported and guided me in my decision to walk the hallways of schools in a capacity that I was once told was beyond my reach. I have learned that man can set ceilings on one’s capacity but has no power over our destiny. Through the Grace and Love of our Creator and our heavenly and ancestral Spirits, we can flourish beyond our imagination. My journey was not a conventional one but, it was my conventional path to walk.”

About Kari Harper

“I am Kari Rochelle Harper an inherent member of the Mistawasis Nehiyawak, on Treaty Six territory. My relationship to my inherent sense of place (passed down to me through my ancestors) connects me to their traditional teachings. I value the inherent identity instilled in me through the experiences of my parents, grandmothers and grandfathers, and their sense of place, and connection to the land. I value my familial teachings and uphold spiritual practice as the core of my existence.”

In 1999, Kari and her mother, Valerie, walked the convocation stage on the same day, Kari with a Bachelor of Education and Valerie with a Master of Education. In 2018, Kari and her sister, Shawn, walked the convocation stage together, both earning their own Master of Education degrees. Sharing the stage with these humble and powerful women was an immense honour for Kari, and she looks forward to watching her mother and sister cross the stage once again as they complete their Doctoral studies.

As one of three educators in her immediate family, Kari has the platform to speak truths and share in redirecting the past and present school experiences of Indigenous children to reflect a stronger sense of identity, well-being, and belonging. She is in her 20th year of educational practice with the Saskatoon Public School division as an Early Learning Kindergarten Educator. In her teaching practices, Kari works to right the wrongs of the Residential School era by teaching truths and honouring the lives lost and stolen by colonial Canada.

As a descendent of residential school survivors, Kari feels the lasting impacts of the residential school system still today. Her grandmothers were stripped of their Indigeneity and forced to assimilate in a colonial state, losing their own language in the process. Kari is slowly learning to speak Nêhiyawêwin, the language of her ancestors gifted by the Creator, and is regaining her own Indigeneity.

Educating early learners has provided Kari with the opportunity to redirect educational practice to include the narratives and perspectives of the inherent peoples of the land on which Canada sits. By engaging students, parents, community members, and colleagues, Kari builds deeper relationships built on the foundations of mutual respect and trust. Over the past 20 years, Kari has managed to bring about meaningful changes and directly impact families in the communities she serves.

When Kari reflects on her own experience as an Indigenous child attending public school in the 1970’s and 1980’s, she was not visible, she never heard the languages of the First Peoples spoken in her classrooms. Her ceremonies were never visually practices and she faced racism because of her brown skin. Today, she works to flip the narrative and promote Indigenous Truths and Experiences within institutions. She is an advocate, an influencer, and a soldier of Reconciliation.

“The families which I served have a better understanding of who we are as Indigenous people, they have experienced the love that forms our Nations through the relationships and reciprocal love felt by their child for me and me for their child. They have partaken in traditional ceremony, and dance. They know about the Residential School era, they know about Treaty, they know about The Seven Sacred Teachings, and they know of the importance of relationship. If a 4- and 5-year-old child learns the history, and hears the truth, it creates a rippling effect and changes the trajectory of narrative and perspective. It is the first step in Reconciliation, and I get to play a part in influencing that path forward. May you always walk the path forward, hope for a better future and do all things with love for one another.”

About Shawn Sanderson

“Tanisi, Shawn Sanderson nitisiyihkâson Mistawasis Nêhiyawak ochi niya nikotwâsik tipahikan askiy. Within me resonates the ancestral narratives of resilient leaders, wise healers, and fervent seekers of knowledge. Their legacy of resilience and persistence profoundly shapes my identity. Reflecting on my life's purpose, I distinguish a rich tapestry of diverse encounters that have guided me to my present state. This trajectory symbolizes my quest for harmony and my unwavering commitment to Indigenous rights.”

As an Indigenous researcher and life-long learner, Shawn acknowledges the crucial role of Indigenous research in educational leadership. Her research philosophy emphasizes Indigenous perspectives, knowledge structures, and approaches, offering deep insights into the cultural social and historical backgrounds that impact educational experiences. Shawn believes that by equipping educational leaders with culturally aware tactics, Indigenous research confronts colonial impacts embedded in educational systems, promoting inclusivity and equity.

Growing up in Calgary, Shawn experienced racism first-hand, sparking questions about her identity from a young age. Shawn’s mother, Valerie, offered support as she learned to navigate life as an Indigenous person, but discrimination and marginalization persisted. Shawn would draw upon the wisdom of her Nohkumak (grandmothers) and kicâpan (great grandparent), who encouraged her to pursue education in the ‘white man’s way’, despite her negative experiences.

After relocating to Saskatoon, Shawn was treated harshly by her peers and began to further understand how society and it’s structures and prejudices affected her. She soon chose to drop out of high school, until impending parenthood compelled her to reconsider education.

Influenced by her mother’s career as an educator, Shawn eventually began working in an inner-city school, where she witnessed immense disparity in educational opportunities for Indigenous students. This experience ignited her passion for challenging and reshaping educational paradigms throughout society.

Shawn’s educational journey embodies a request for understanding, resilience, and advocacy. Rooted in her Indigenous heritage, Shawn works to challenge systemic injustices and nourish environments where Indigenous voices are valued and empowered.

Throughout Shawn’s undergraduate and graduate studies, delving into Indigenous Studies has been a particularly profound journey. Indigenous perspectives emphasize interconnectedness, reciprocity, and holistic approaches when it comes to parenting and child-rearing, which sharply contracts mainstream Western paradigms. By incorporating Indigenous perspectives into child-rearing, educators can better nurture cultural identity, resilience, and harmony, bridging the gap between conventional educational models and Indigenous wisdom.

Shawn believes that embracing Indigenous knowledge and perspectives is transformative. By centering Indigenous wisdom and educational leadership, researchers honor Indigenous heritage and pave the way for more equitable and inclusive educational systems. For Shawn, it’s imperative to respond to the call to action by engaging with Indigenous research and supporting Indigenous scholars. Amplifying Indigenous voices and advocating for their inclusion in educational leadership are essential steps toward the future where Indigenous perspectives shape educational policies and practices.

“The memory of câpan Solomon’s wise words infused with his profound Indigenous wisdom and ancient resilience, resonates within me today. I know if he were here today he would tell me, “Nosom, you come from a lineage of great leaders,” he reminds me, “Mistawasis, ekwa Ahtakakoop, ekwa Ayahsoo, ekwa Broken Jaw, ekwa Kaskitêwi-Maskwa-Iskwêw, ekwa kohtâwiy, ekwa nikâwiy, your ancestors watched over you as you smudged this morning, acknowledging your calling. You are Nehiyaw. Speak from the heart. Know that you are not perfect, no one is. Know that you can do this. Kimaskawisin.” toward the inclusion of Indigenous people, and equity in educational leadership. Let's pledge to cultivate environments where Indigenous wisdom is honored, cherished, and woven into every educational facet. Together, we can drive meaningful change, embracing diversity, nurturing empathy, and empowering Indigenous scholars, society, and communities to flourish.”

Nicole Mercereau is a Métis-Ukrainian Master's student in the USask Department of Educational Administration.

Originally hailing from Duck Lake, SK, Nicole is the first in her immediate family to attend university.

As a child, Nicole loved research and learning more about subjects that interested her. As a graduate researcher, Nicole gets to do the same things that she enjoyed as a child, on a larger scale, with topics that fuel her passion.

Nicole convocated from Saskatchewan Urban Native Teachers Education Program (SUNTEP) in 2004. SUNTEP's recognition and support of Nicole's Métis identity ignited a passion for her heritage. SUNTEP was an inclusive, safe place where she could be her authentic self. SUNTEP provided the missing cultural piece that allowed Nicole to be more aware of Indigenous issues through the unique programming she received throughout her Bachelor of Education. This strong foundation has been the catalyst behind her return to graduate studies as she's begun to view the world through a different lens as a parent with Métis children who are in the education system.

After an 18-year hiatus from education, Nicole believed that further education was the key to a better life for her family and would allow her to make a better world for her Métis children (Georgia, age 5, and Dominic, age 8) and community. After completing her Master's, Nicole plans to begin her PhD studies, with the long-term goal of remaining in post-secondary education to teach and conduct research.

Nicole feels blessed to be supervised by Dr. Gordon Martell, who has done noteworthy work for Indigenous education both locally and across Canada. He has provided Nicole with strong support and guidance with his vision and experiential knowledge.

In addition to being a graduate student, Nicole is a research assistant for Métis professor Dr. Carmen Gillies, who has been an influential mentor for her as she learns more about research. Throughout her graduate studies journey, Nicole has been a graduate teaching assistant in the College of Education’s Educational Foundations and Educational Administration departments.

Nicole's research focuses on Métis education in publicly funded education through a contemporary and historical lens by revisiting generations of Nicole's family's educational experiences as Métis learners. Historically, educational systems have not been kind to Indigenous people, and through addressing systemic barriers and biases, more equitable education can be realized.

By addressing shortfalls in policy, Nicole looks forward to a future where my Métis children can see themselves reflected in school curricula as opposed to a tokenistic, sprinkling of content. She hopes to use her privilege of higher education to make a positive change for the Métis community.

Notable USask Awards:

- 2023 Indigenous Scholars Award (Social Science and Humanities Research Council)

- 2023 Gordon McCormack Memorial Graduate Scholarship for Native Students (College of Education)

Jennifer Amarualik-Yaremko is an Inuk MA student in the USask Department of Political Studies.

Jennifer lived in Nunavut until the age of 8, and then moved to Alberta in pursuit of a better education. She was shocked by the quality difference between the Nunavut and Alberta educational systems, and she wants to provide every Inuk, Métis, and First Nations child with the same opportunities she had. Her work focuses on decolonizing education policy in Nunavut and advocating for a stronger Indigenous voice at decision-making levels across all sectors of research, development, education, and service delivery.

Jennifer thinks that real decolonization of any institution cannot happen without Indigenous people. She also thinks that we have a duty to honor the Treaties and the people who came before us, so she is always working to end structural ignorance and make it easier for people with diverse viewpoints to understand and learn from each other.

Notable USask Awards:

- 2023 Award for Community Engagement (College of Arts & Science)

- 2022 Mabel F. Timlin Award for Indigenous Students in Political Studies (College of Arts & Science)

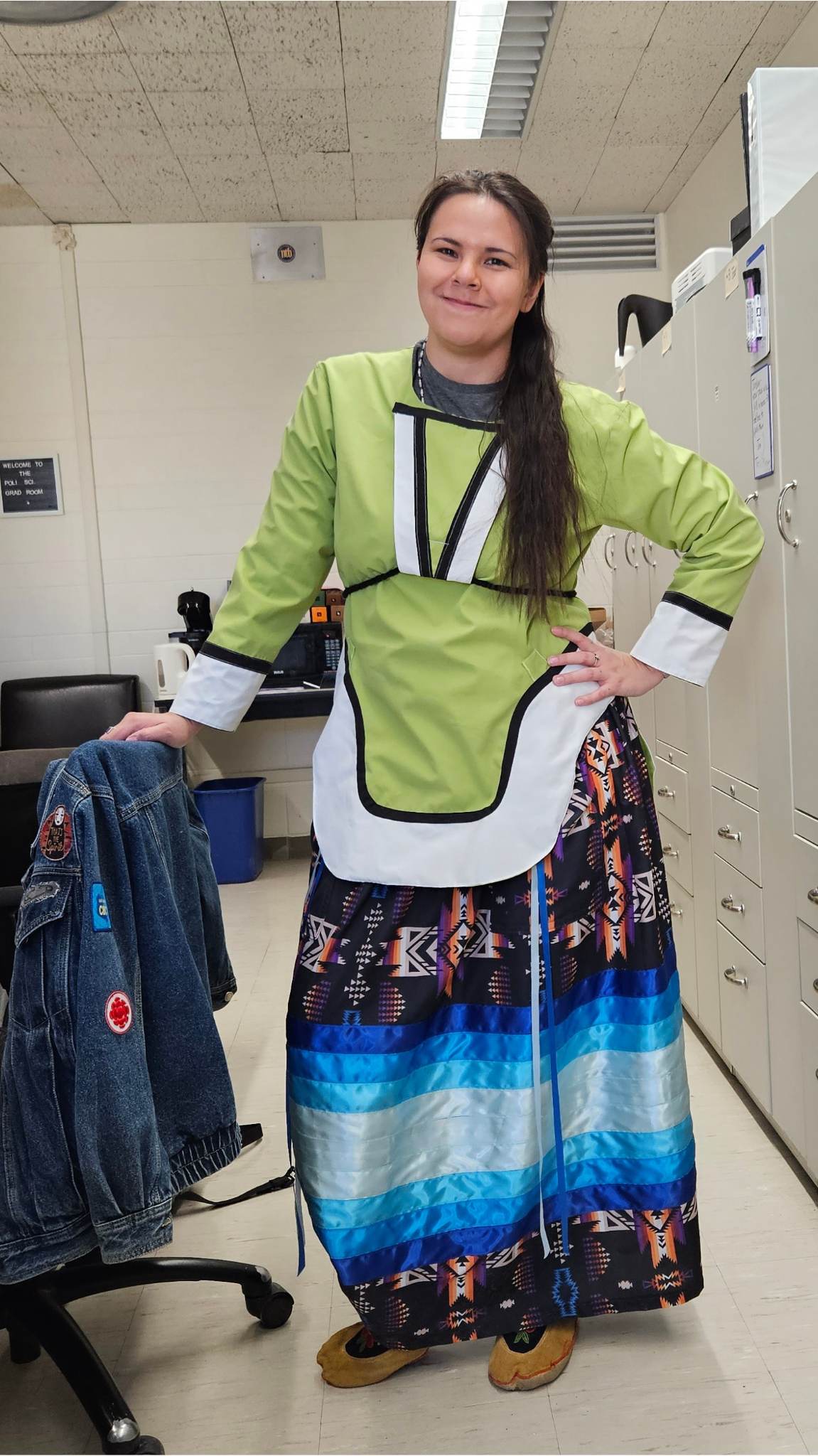

About Jennifer's Regalia

Jennifer takes great pride in wearing her traditional regalia in her day-to-day life, as well as for life's significant moments. In the provided photo (right), Jennifer explains each piece of her regalia and what they mean to her:

"My necklace is a piece of beadwork done by my mom's sister, Najalaa/Salome Amarualik, before she was lost as one of our Missing and Murdered Indigenous women. I wear it to big events like graduations, talks and presentations I give, as she is one of my namesakes and I feel the need to represent her in my life's events.

"The green top is in the traditional Inuit style of an amautii, a woman's overcoat that traditionally has a space in the hood for a child. However, my grandmother made me that coat for me without the hood on purpose, as I'm supposed to be in school! It's waterproof, windproof, and the tie can be tightened or loosened like a belt.

"The moccasins were saved form a thrift store by my mom, they feature traditional Southern Canadian Indigenous flowers and plants beaded on the vamp and going up the boot along the ankle. They also have summer rabbit fur pompoms on the strings that lace them up.

"My ribbon skirt was picked out for me and bought from the Wanuskewin gift shop for my birthday this year. It's still special to me despite the relative lack of familial history, as it has pockets!"